“There is nothing new except what has been forgotten.”

Marie-Antoinette

Nov 2, 1755 – Oct 16, 1793

Marie-Antoinette, since her life in the French Royal court in 1770, left behind a trail of creative whims in her support of many artists until her execution in 1793. The Queen also took time for self-expression in many art forms, even laying a brush to paper with her watercolors. Although this trail has yet to reveal solid examples, there is evidence that she owned a watercolor box, and treasured her paintings before they were lost to time and the overturn of the French Revolution.

The Comte de Paroy, Jean Philippe Guy Le Gentil was a miniaturist and engraver that found favor in Marie Antoinette’s court. She sought his talent to paint concepts she created for art to send to her sister, The Archduchess Marie-Christine, most likely for the Albertina Museum, after a folly over adding a humorous scene over one of her paintings. The Comte documents his experiences with the Monarchy in Mémoires du Comte de Paroy : Souvenirs d’un Défenseur de la Famille Royale. In his memoirs, he mentions a painting of Marie-Antoinette’s. He comes across her “color-box” or watercolor box with a watercolor “drawing” in it, and reprimanded mischief follows:

The queen came after dinner at the house of Madame la Duchesse de Polignac, or, more exactly, at the house of the Dauphin, of whom she was governess. One day, she had a small watercolor drawing brought that she had made in the park of Trainon. She left this drawing on a table in her colour-box and went to play a game of trictac with the Princesse de Lamballe and the Baron de Viomenil. I took advantage of this moment to remove the colour-box and passed into Madame de Polignac’s cabinet. There I hurried to add at this sight a small scene which I had witnessed at the same place. A few days before, the queen had in the afternoon, we took a walk to Trianon, to see the work that she had ordered there. She was next door of a small workman who carried grass in a wheelbarrow; she said that she wanted to boast of having worked valiant in his garden; she took the wheelbarrow from the hands of this young digger and began to push her. She had not attention that this land was sloping, so that the wheelbarrow dragging her away faster than she, the queen let her go, laughing. We were more behind her, and we ran up. The Duke of Villequier arrived first and said to him very seriously: Like the drawing represented the View of this slope, I painted there quickly the scene where the queen Dropped the wheelbarrow in laughing, and where the Duke of Villequier Get up spoke to him. The duke was easy to be recognized, small, with wide shoulders and short collar. It was all the more striking resemblance in its appearance that the others per- soundings were small figures of six or seven lines. This work took me only two hours. After the trictrac, the queen had been playing billiards in a gallery next to it. I put the drawing back in the box, without being noticed, and Madame de Polignac had it reported to the queen. The next morning, Madame de Polignac sent me a footman to Paris beg me to come to Versailles without fail before ten hours. I was exact at the appointment. “My cousin, she said to me very seriously, the queen is furious against you for what you have taken the liberty of adding figures to this drawing. She has charged me with the task of testify and defend yourself from running in front of it. So you can no longer find at my house at the hours when she comes. “This “It is not possible,” I replied, “according to the knowledge that I have of the queen’s character. I believe, in the opinion of the milking, which she will have been very happy to see represented on his drawing the line of the event of the wheelbarrow which had made him laugh so much; Besides, no one but she, in outside of you and me, cannot know that she has not painted this little adventure. She can be sure of my discretion. “You are right,” replied Madame de Polignac; last night, the queen sent for me and sent for me. showed her drawing, which had no face when she had brought him down to my house. As she had questioned and that none of them could tell him how could this drawing have been touched, she asked whether, among my society of yesterday, I did not suspect that I had I don’t think anyone has done these figures.

I thought of following you, and, as I hesitated to name you, the queen said to me kindly, “But speak; I don’t I’m not angry; I think we filled it wonderfully the space that remained free on the front of the painting, and moreover, I recognized the Duc de Villequier by his appearance and Madame la Comtesse Diane. “Well, madame, I will confess to your Majesty that I believe that the culprit is one of my cousins, the Comte de Paroy, who is painter; I cannot suspect that he . — “I charged with knowing; and make him believe that I am very angry. You will scold him loudly, but deep down I think what he did well, and I saw it with pleasure. I don’t want him to talk about it, tell him. Therefore, my cousin, I warn you of all this. I have told you sent for early to inform you of it; stay to breakfast with me; I am sure that the Queen will not be long in coming, but do not appear to be know that she is not angry. “Around noon, the queen entered the house of Madame de Polignac, who was writing, while I was looking at a large book of prints representing views of Switzerland. I got up and stepped back into an embrasure of the window; the queen, as she passed me, glanced sternly at me and went straight to Mme. de Polignac, to whom she asked if she had spoken to me: “Yes,” she said; his answer is that it did not come to him in the idea that your Majesty might lack him. Oh! “I believe so,” continued the queen, “call him.” Madame de Polignac made a sign to me to approach; I obey, with a respectful and eager air. “You draw well,” said the queen, smiling; you have proved it to me yesterday on my little drawing. “Madam,” I replied, I had witnessed the scene that I have traced there, and which “had made your Majesty laugh; I thought that she would not find it not bad to see the memory of it recalled on the same place where it had happened. “Madame de Polignac has scolded you, has she not?” “She followed your Majesty’s orders, but I had trust in his goodness to recognize that my intention had been to do something that would be pleasant. “You had a good idea; I’m going to send this drawing to Brussels to my sister; I’m sure that it will please him. I also want to show you some other little subjects of emblems that I gave him address. She sent for them; I say to the queen that I was familiar with these sorts of subjects, to which I had particularly practiced myself in my society. “Well,” cried the queen, “I have several in the idea, I will give them to you, and you will make me pleasure of rendering them as you will design them. I replied that I considered myself as honored how fortunate that my talent could be agreeable to him. The queen gave me about twenty to do different times. She thought I had done well rendered what she desired; it has sent several to her sister the Archduchess, that she loved very much.

Jean Philippe and Marie-Antoinette’s painting story seems to end after it was sent to her sister. Perhaps, a humorous scene of the Queen duped by a wheelbarrow may not have been fitting for view at a museum. However, it is a poignant view into her character and sense of humor, unafraid of making fun of herself. This transparency of a Monarch invites the want to find more of her paintings, to discover more of her. But her paintings seem to be unavailable, except perhaps one.

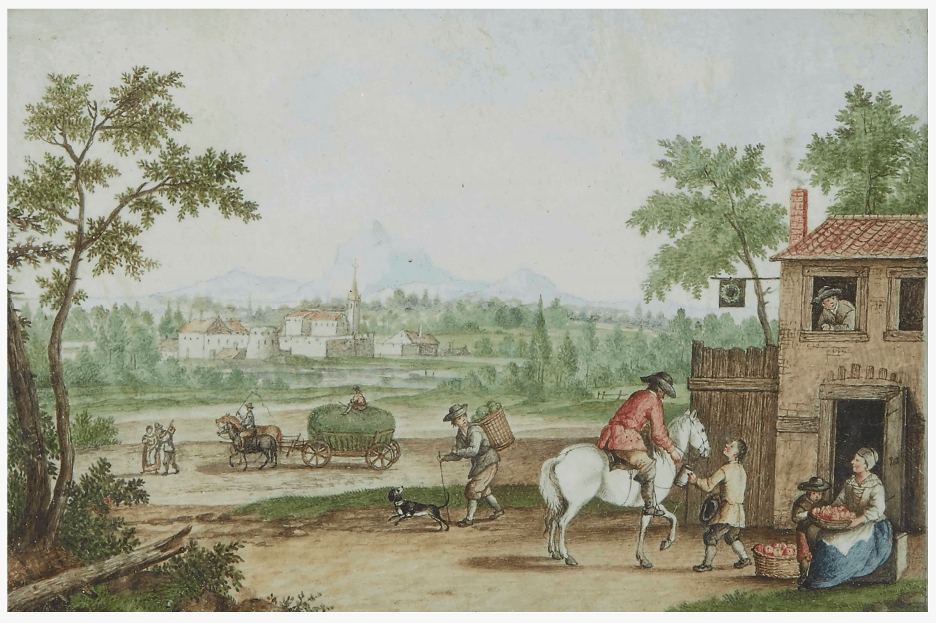

Christie’s in Paris auctioned a watercolor thought to be by Marie-Antoinette when she was still Archduchess. A written statement on the reverse of this watercolor states it was produced ‘by the unfortunate queen Marie-Antoinette who was decapitated on 16 October 1793’. “The pastoral scene depicts a small church, pond and hay wagon, a rider in the foreground seeking refreshment at a local tavern” (Christie’s). This charming scene may show a royal that thought about the world outside of the safety of her estate, however idyllic. Marie-Antoinette was quoted, “There is nothing new except what has been forgotten” (Edinburgh). Perhaps her paintings will be made public and become once new to our forgotten eyes, revealing the innocent imagination of Marie, before charged as a guilty queen, who once charmed a nation.

Bibliography

“Education of the Poor in France”. The Edinburgh Review, or Critical Journal, Vol 33. Google Books, Google, 1820, p498. https://books.google.com/books?id=7UY7AQAAMAAJ&pg=PA498#v=onepage&q&f=false

Gentil, Jean Philippe Guy Le – Marquis de Paroy. “Mémoires du Comte de Paroy: Souvenirs d’un Défenseur de la

Famille Royale. Google Books. P269-272. (French translated by Word) https://books.google.tt/books?id=1M4-AAAAYAAJ&printsec=frontcover#v=snippet&q=aquarelle&f=false

Gentil, Jean Philippe Guy Le, et al. “Jean Philippe Guy Le Gentil, Comte de Paroy: Portrait of Vigée-Lebrun.” The Metropolitan Museum of Art, Accession Number: 24.80.305 http://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/385760.

“Marie-Antoinette — A Life in 7 Objects.” ARCHIDUCHESSE MARIE-ANTOINETTE D’AUTRICHE (1755-1793), Paysage Avec Auberge | Christie’s, Christie’s Paris, www.christies.com/lot/lot-archiduchesse-marie-antoinette-dautriche-paysage-avec-auberge-5942045/?intobjectid=5942045&lid=1

Unknown Artist. Marie-Antoinette, after 1783. after Élisabeth-Louise Vigée Le Brun. National Gallery of Art. Accession Number 1960.6.41. https://www.nga.gov/collection/art-object-page.46065.html

Thank you!

Subscribe

Enter your email below to receive updates.